A rainy day in Whittier

USA - 2016

Overlooking a bay in the center of the highest glaciers of Southeast Alaska, in the middle of the Cougach National Forest, Whittier is home to 230 people, the destination of many lives fleeing from civilization or searching a radical isolation in the wilderness.

Whittier is a vertical town where 90% of its population live inside a 15-story apartment

building called the Begic Tower and built by the US Army during the Cold War in the 50s, a

former strategic anti-Soviet outpost. When it was dismantled the families living there

decided to buy the property.

The “One City Under one roof” has endured, back in 1964, the second most powerful earthquake

recorded in the history of mankind. The inhabitants of Whittier are isolated from the world

because to enter town there’s only a narrow one and a half mile long tunnel that’s closed

every night.

Marzio G. Mian

The sound of silence | 2

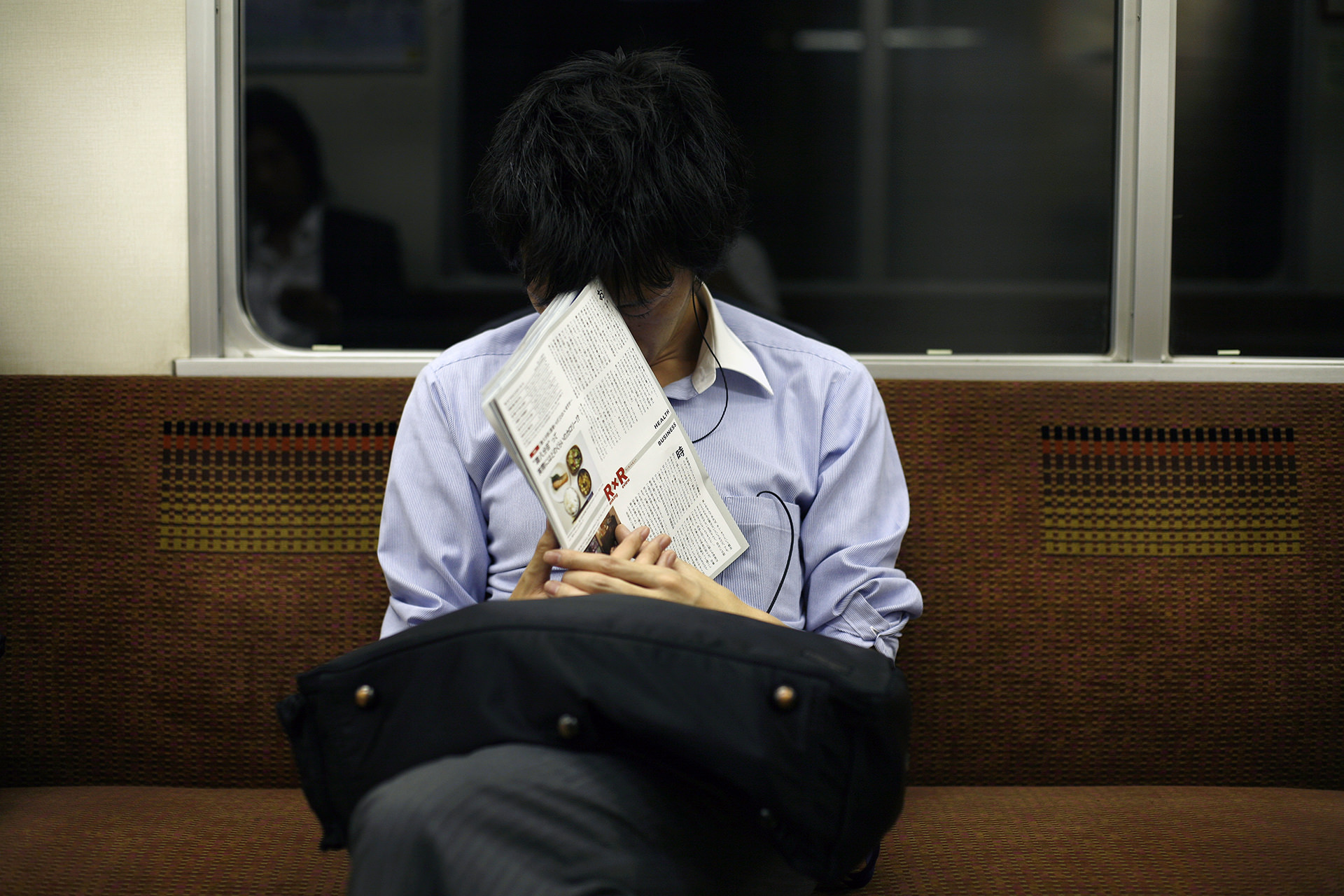

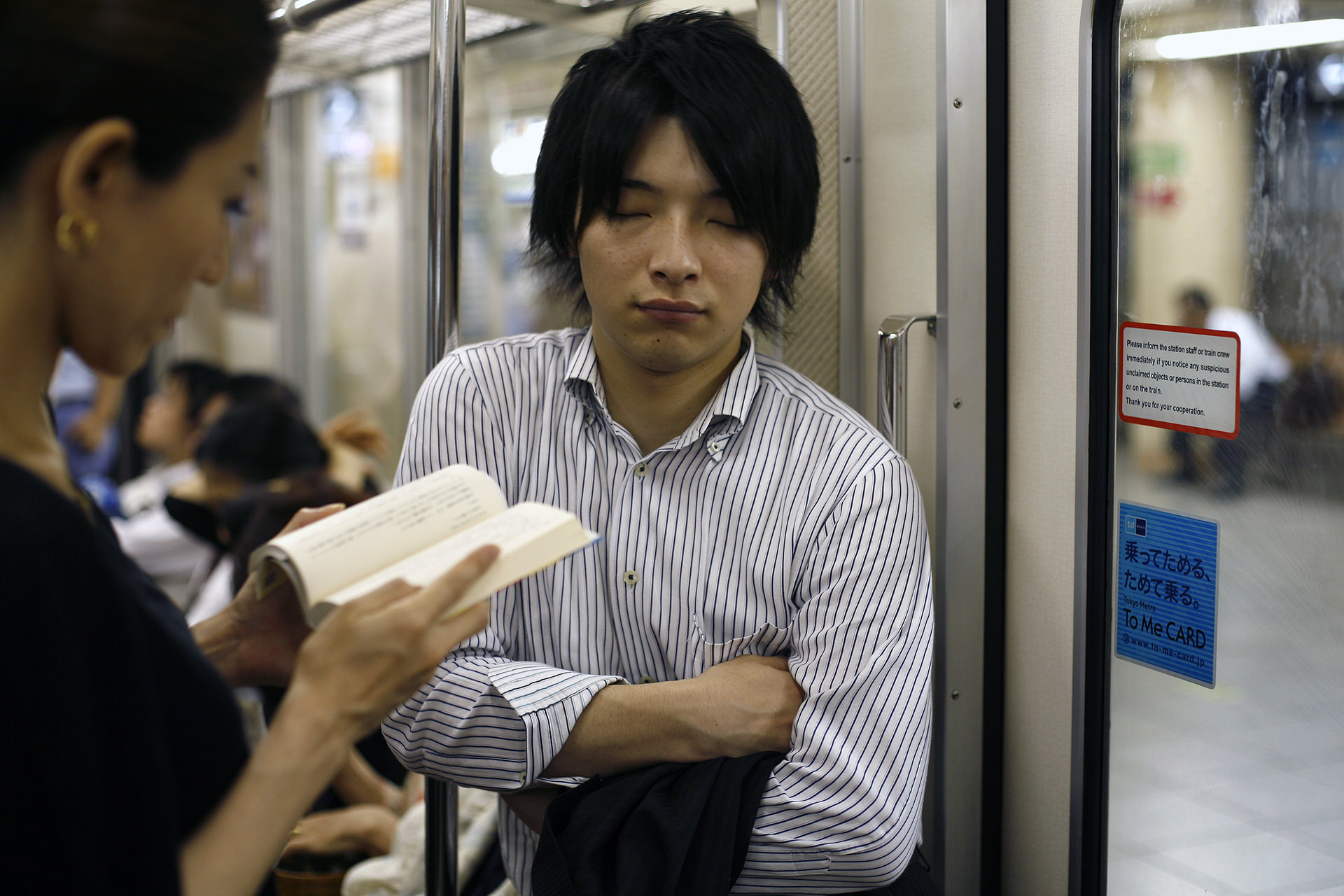

Japan - 2016

Second and third generation smartphones where launched on the markets around ten years ago but Japan was one of the least country to step in the game. Despite the country’s long time enthusiasm for digital technology, Japan’s users stuck with feature phones much longer than those of many other countries. Tokyo, where the population in the greater metropolitan area is around 38 millions, has a subway system that accommodates roughly 8 million passengers a day with a wi-fi service good enough to stream videos. The average subway commuting time is one of the highest in the world and in a country with a very formal and respectful culture, the subway is no exception: there’s hardly any noise pollution.

Not very long ago, back in 2008, I was in Hokkaido, Japan, to shoot the G8 Summit in Toyako and a story on the Ainu indigenous minority. I also spent a couple of weeks in Tokyo and I noticed that many many people, of any age and social class, when riding the subway would easily fall in a deep sleep and magically wake up always in time to get off the train exactely where they had to. The Tokyo subway was very quiet, there was a lot of silence. In 2016, while I was in Tokyo after I came back from Naraha in the Fukushima Prefecture, I moved around using the subway and after a few rides I noticed that, even though people commuting spent most of their time on their smartphones, there was the same silence I had experienced on the same metro lines when, back in 2008, I shot a series of portraits of Tokyo commuters sleeping deeply while riding on the trains. That silence was familiar in some way so I decided to shoot this new sort of twin series of portraits.

Almost 8 years have passed and the Tokyo subway’s still very quiet and there’s still a lot of silence. Things have changed though: people don’t sleep no more, they are too busy with their smartphones.

Alpine borders

Italy - 2016

What is the situation at the Italian borders? What are the relations with our neighbors? Who are and how live the Italians living on our borders? Marzio G. Mian and I have traveled along the entire Alpine frontier, from Ventimiglia to Gorizia, to see if, on the wave (or the excuse) of the refugees emergency, also in Italy is returning that twentieth-century bordering feeling, separation and even opposition which is blowing nowadays in much part of Europe. A sort of nostalgia of sovereignty – and often nationalism – that is leading back to formulas of closure in the old Continent once again. What about Italy? This journey through these marginal and often neglected regions was a wonderful opportunity to put at the center of our investigation the humanity that inhabits them, in Italy and on the other side of the border as well. A great occasion to encounter the men of the Border Police and those of the Corpo Forestale, to discover the submerged cross-border economies and to meet the new Mayors, who are becoming cultural ambassadors, as well as the young people who renounce to the appealing contemporaneity to keep alive their communities and way of life. A journey that also served to denounce the abandonment of this remote part of Italy, which lives modern emergencies in solitude, from the drama of migrants to climate change to the depopulation of the alpine villages.

The River of Giants

Marocco - 2015

From the excavation site of the sauropods near Remlia to the mountains around Iferda N’Ahouar, all the way til the Zrigat excavations, where the Spinosaurus was found. The story in pictures of the expedition in the south-eastern desert of Morocco organized by the National Geographic Society with the Civic Natural History Museum of Milan in April 2015

Spinosaurus (meaning “spine lizard”) is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived in what now is North Africa, during the lower Albian to lower Cenomanian stages of the Cretaceous period, about 112 to 97 million years ago. Spinosaurus was among the largest of all known carnivorous dinosaurs, possibly larger than Tyrannosaurus and Giganotosaurus. Among the most valued of the finds are dinosaur bones from the Kem Kem beds, a 150-mile-long escarpment harboring deposits dating from the middle of the Cretaceous period, 100 to 94 million years ago. This genus was known first from Egyptian remains discovered in 1912 and described by German paleontologist Ernst Stromer in 1915. The original remains were destroyed in World War II.

After a young paleontologist named Nizar Ibrahim tracked down in 2013 a fouilleur – a local fossil hunter who sells his wares to shops and dealers – who was able to help him discover a new set of bones belonging to a young specimen of Spinosaurus, he’s had the chance to go back to the excavation site in order to collect all the remains he could. The pictures of this reportage are the documentation of his last expedition in the Kem Kem desert.

It’s sustainable tea time!

India - 2012

Assam, Darjeeling, North Bengal and Nilgiris are the four best quality of tea produced in India, the largest producer in the world. The Nilgiri is the only one produced in South India. On the hills of this region the most famous and valuable variety of the world’s tea is grown, largely intended for the European markets. In this district of Tamil Nadu the main production is done in Coonoor, Kotagiri and Ooti and their surroundings, where there are some 3000 hectares of land cultivated for the production of tea. Here the economy revolves almost solely around this industry. Every year they collect about 37,000 tons of leaves from which, after the production process, around 8,500 tons of black tea is produced.

3,500 workers between 18 and 58 years, two-thirds of whom are women, work in the area and the crops depends on the existence of thousands of families. Over the years the consumption of tea and its demand in the world have grown steadily. The tea industry has done the same but in a more than proportional way, giving rise to a physiological oversupply and the consequent fall in prices obtained on the market primarily from smaller producers. In July this year, despite an increase in GDP of 7.2% for the Indian economy, auction No. 23 of Coonoor Tea Trade Association, 42% of the half million kg on offer they remained unsold. Despite the economic crisis, in this rural area of India there’s no shortage of good news. The eight largest estates in the area, members of the cooperative Container Tea and Commodities, in 2009 received a sustainability certification from The Rainforest Alliance, a non-governmental and international independent organization.

Glensdale, Havukal, Coonoor, Kairbetta, Dunsandle, Sutton, Parkside and Warwick plantation estates are those where Lipton buys the tea for the famous varieties Yellow Label and Earl Grey. The estates of the Nilgiri are the second, after those of Kericho in Kenya, to have achieved this important certification and today the tea in the filters of these two qualities is 100% from plantations that meet the strict criteria of the Sustainable Agriculture Network whose pillars are environmental protection, social equity and economic viability.

The certification means, in practice, less pollution thanks to a controlled use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, reforestation to reduce soil erosion, improving of environmental and wildlife protection, less pollution thanks to the composting practices of production waste, increased awareness of workers in the use of the waters and in the management of recyclable waste. Similarly certification is a guarantee of improvement of living conditions of the workers’ families due to the housing programs, drinking water supply, schooling and medical care.

Down under

Australia - 2010

A grand tour on the biggest island of the world, which is also the smallest continent on

the planet.

I was contacted by writer and blogger Pulsatilla to go with her on this

three weeks journey around Australia. Just a tourist trip to discover one of the weirdest

place on earth, where you can find the most beautiful scenarios and the most dangerous

animals of the world in just one (huge) place.

The reportage was commisioned by MAX

magazine.

The sound of silence | 1

Japan - 2008

Greater Tokyo Area is the world’s most populous metropolitan area with its 35,327,000. A lot of people. Moving. Japan is a country that surely recognize the many advantages of rail transport, including its convenience, energy efficiency, low pollution, and safety. Every day millions of Tokyo residents commute from their houses in the suburbs back and forth to work or to school. There are 13 subway lines in Tokyo, many of them are linked up with commuter lines and extend their service to the suburbs. They currently carry more than 7 million passengers per day. On an average base they spend 74,5 minutes to go one way from home to work. Two hours and a half on a train, every day, is a lot of time. Specially if we consider how much time most Japanese people spend working. 28 percent of the people living in Tokyo work more than 50 hours a week. Some 16 percent double their weekly hours schedule working overtime. In the last ten years more than 30.000 people died because overworking. Occupational sudden deaths. Those who don’t die commute on trains. And sleep. At any hour of the day. People of any age, occupation, social class, suburb. They get on the train, find a seat and sleep till the stop they have to get off at. Even if it’s just one.