Article 15: debrouillez-vous

Democratic Republic of Congo - 2011

Electricity and an ambulance. Drodro’s hospital, framed into the forest that covers the hills in Oriental Congo, has both these commodities, a rarity in this part of the world. This could be the picture of a lucky infrastructure but it’s not: Drodro and its hospital are the best example to explain today’s Congo, a puzzle where tiles don’t match or, more likely, are gone missing; in first instance the war, more recently because of a CentralPower which at best is absent, at worst rapacious. The DRC is very rich of minerals but is also lying at the very bottom of the UN’s Human Development Index, 187th country out of 187. It’s not a coincidence. “We have electricity but there’s no running water and we’ve got to walk two hours to reach the closest spring”. Jean Diropka Lona, 38 years and Drodro’s Hospital manager since 2010, is a flood of words. “We have the ambulance but what for if nobody can call the hospital, considering there’s no line, and besides that, the roads are in a terrible state? A total disaster”. Lona doesn’t stop. “In the intensive care unit there’s nothing to reanimate children, in the laboratories there are no chemicals or tools, the surgery room is unequipped and we have no medicines…we’ve lost all that we had during the war, we managed to recover some mattresses from the refugees’ camps”. His hospital covers an area of 1.100 km² and serves a population of 140.000 people with an allocation of $3.000 a month, “at the end there we left with only between $20 and $40 which are not enough to pay the staff that should be paid by the Government…”.

Débrouillez-Vous – fend for yourself – is the 15th Article of the DR Congo’s

Constitution, the only unwritten article and the only one that everybody knows. Lona

like all the other tens of doctors and nurses that work in Bunia, Tchomia, Lita,

Mongbwalu, in the cities and villages of Ituri, the district along with North Kivu that

most evidently carry the scars of the civil war, have to fend for themselves. They’re

helped by international assistance programs that are slowly abandoning the region

because the conflict belongs, officially, to the past, even though a recent one. The

same have to do tens of thousands patients who are attended by those same hospitals and

rural health centres.

Not always, though, to fend for themselves is enough. In 2003 in Lita, half way between

Drodro and Bunia, the capital of Ituri, the Lendu ethnic militias have killed with

machine guns and machetes more than 10,000 people, most of whom were of Hema ethnicity

while many others were Lendus who tried to protect them, in the great Church and between

the parish and the hospital. The health facility reopened only in 2008 while the Church,

profaned by the massacre, has been rehabilitated to the cult in 2011. In 2006 and 2007

Michelin Kisai, pregnant, knocked at the hospital’s door but there was no one who could

take care of her fetal distress. Both children were stillbirths. Now the doctors have

come back and are taking care of her fourth pregnancy but the roads are still missing

and so is the rest.In Ituri, the war is finished in 2008 but its traumas have not been

reabsorbed. Infrastructures don’t exist, electricity and water malfunction, there are no

medicines, medical and laboratory materials. The staff at the hospitals, often working

unpaid, is unqualified and unsecure while illness and violence are all too present. The

first victims are women and children. Endemic malaria, high rates of HIV infections,

gastrointestinal diseases, tuberculosis and malnutrition. A tragic scenario, fuelled by

the cultural limitations that delay access to health facilities, and by the direct and

indirect effects of the conflict such as hundreds of orphans and the rise of rape, a

weapon of war converted by ex-militiamen and by connivance into a peace practice.

© Alberto D’Argenzio

Mariabasti

India - 2011

Disability affects hundreds of millions of families in developing countries. Currently, around 15% of the total world’s population are said to be suffering from a disability. Having a disability places you in the world’s largest minority group and as the population ages, this figure is expected to increase. 80% of persons with disabilities live in developing countries, according to the UN Development Program ( UNDP). The World Bank estimates that 20% of the world’s poorest people have some kind of disability and tend to be regarded in their own communities as the most disadvantaged. Poor people are more at risk of acquiring a disability because of lack of access to good nutrition, health care, sanitation, as well as safe living and working conditions. Once this occurs, people face barriers to the education, employment, and public services that can help them escape poverty. Statistics show a steady increase in these numbers. In India, the figure is estimated around 100 million people. Basic services for handicapped people are hardly accessible to less than 5% of the disabled persons.

Families with a low or zero level of education and very low purchasing power are ill-equipped to bring-up the handicapped, who are often considered “a curse from God” or an “unwanted burden”. HOWRAH SOUTH POINT was founded in 1976 by French Father Francois Laborde to help handicapped children and provide a medical support to the most deprived from the slums in Howrah, the industrial suburb of Kolkata. HSP, a non-confessional organization opened to people of all caste, creed and language, has the aim of facilitating the rehabilitation of the physically, mentally and socially challenged back into the mainstream of society. Today HSP encompasses 5 handicapped children’s Homes and 7 outdoor physiotherapy Centers located in Howrah and Jalpaiguri, providing residential care to 275 children among whom 160 are physically or mentally challenged. They are provided with basic needs, food, shelter, medical attention, physiotherapy, education and training.

Maria Basti, among the specialized for spastic, mentally and physically handicapped children centers of Jalpaiguri, is a very unique place. All the 13 girls living there are of age and suffer major mental and physical disabilities, more than 90% in some cases. Solidarity is the main feature of everyday life in Maria Basti. There are precise rhythms, repetitive gestures that give each day a specific schedule to follow in order to lighten the burden for the people who work and live in the center and to make the days for the girls, as much sliding and independently manageable as possible.

Udayan

India - 2011

Since ancient times, leprosy has been regarded by the community as a contagious, mutilating and incurable disease. Many myths and stigma have always surrounded it. Of course, it is not a curse of god. And it’s not hereditary. No child was ever born with leprosy and, contrary to popular belief, it is one of the least contagious of all the communicable diseases, only 15% to 20% of cases being contagious. When ‘Mycobacterium leprae’ was discovered by Hansen in 1873, it was the first bacterium to be identified as causing disease in man. Today, Leprosy is curable disease, at all stages. It is estimated that there are between one and two million people visibly and irreversibly disabled due to past and present illness who require to be cared for by the community in which they live. It is not totally clear how leprosy is spread, although all sources agree that prolonged, close contact is necessary for contracting the disease. It normally thrives in conditions of low nutrition, lack of hygiene, and insanitary conditions.

Thus, in overcrowded slums the incidence of leprosy is much higher than in other establishments. Early detection and regular treatment are necessary means for the elimination of the disease. The diagnosis and treatment of leprosy is easy and most endemic countries are striving to fully integrate leprosy services into existing general health services. Multi-Drugs-Therapy (MDT) must be made available in all primary health centers to enable patients to be treated as close as possible to their homes. This is especially important for those under-served and marginalized communities most at risk from leprosy, often the poorest of the poor. All the children of UDAYAN, located in Barrackpore, are affected by leprosy in some way. Most of them were born in leprosy colonies and have parents who suffer from the disease. About 5% of the children themselves suffer from the disease.

The Center was founded by Reverend J. Stevens who started taking care of eleven children in 1970. After 40 years and 7 thousands children, today Udayan caters 100 girls and 200 boys between 4 and 18. Udayan provides a loving home and an opportunity for a new life – free of the scourge of leprosy and its associated poverty – through education, food, clothing, medical care, access to recreational facilities and vocational training.

Sulma

Honduras - 2009

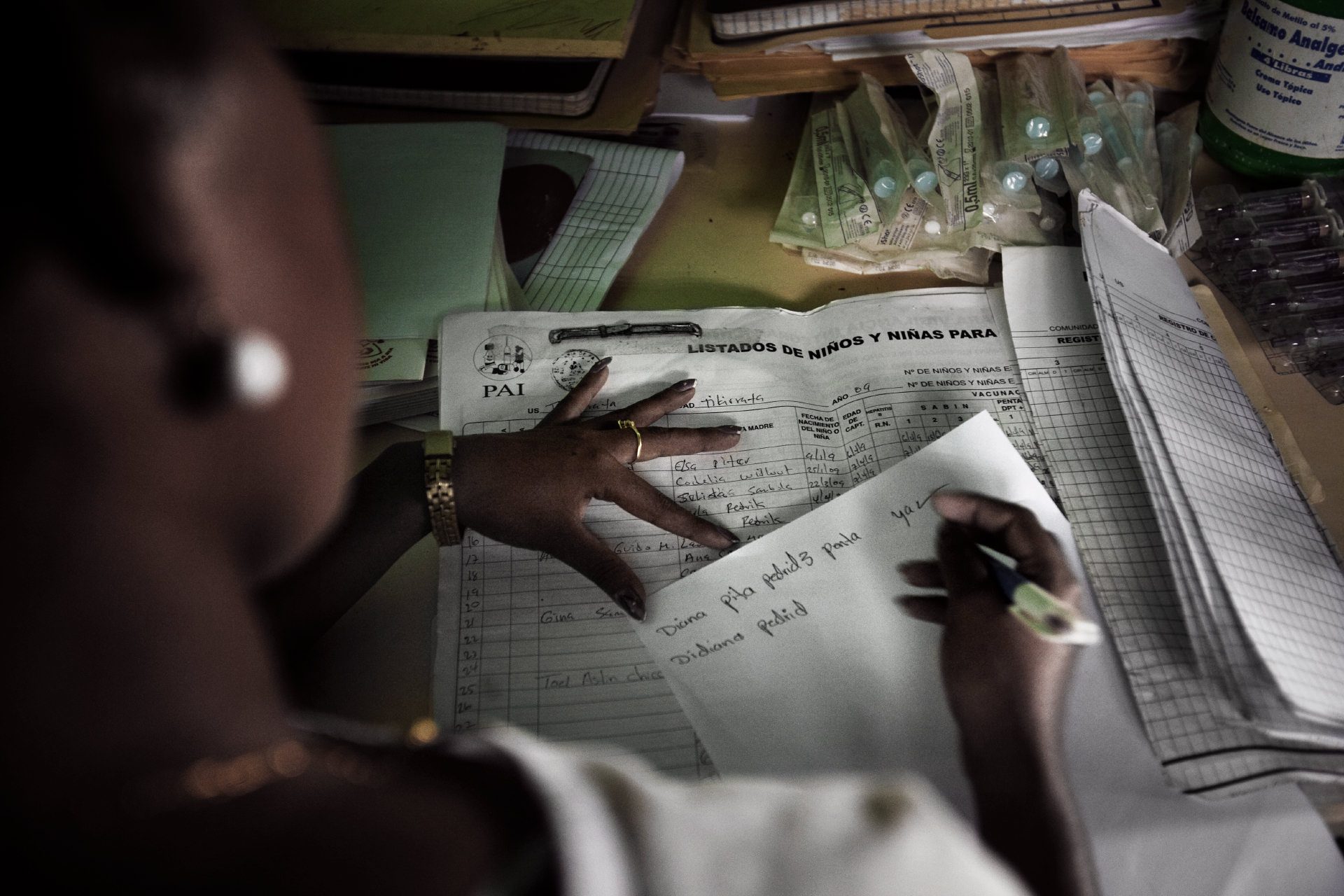

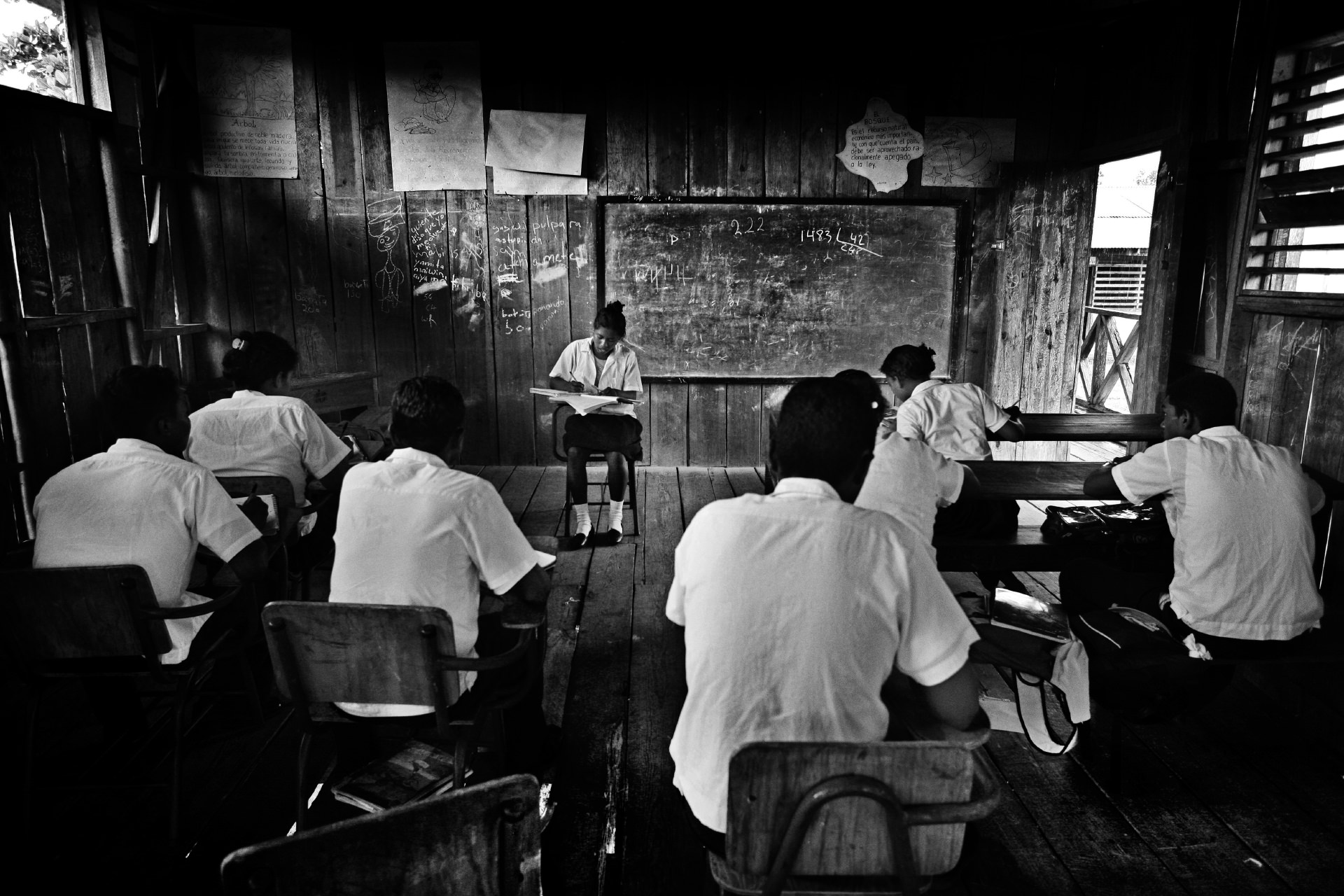

In the honduran Moskitia there is only one hospital in the regional capital city of Puerto Lempira, a remote town that can be reached only by plane or by boat. Puerto Lempira is very poor like all the smaller communities of the proud and kind miskito people. The communities in this rural area of Central America mostly dont't have any kind of medical facility and a small health problem can easily turn into a bigger one.

In Moskitia many kids suffer malnutrition, TBC or malaria. Those who don’t, most of the times aren’t able to attend school because they have to help out their families since a very young age, not only in the house but also on the field doing tough works and handling dangerous tools. Sulma is a 10 years old girl who lives with her family in a small village between Laka and Tikiuraya, in a very remote part of the region. She arrived at the Centro de Salud in Tikiuraya while I was there documenting the construction of the Centro de Salud as part of an NGO project and the images were going to be used to raise extra money in order to to buy a small boat for the doctor of the Centro de Salud so that he/she would be able to bring patients in extreme need to the main hospital in Puerto Lempira, roughly 4 hours of navigation on small rivers away.

Sulma arrived ath the Centro de Salud with her hand wrapped in a dirty rag drenched with blood and fear in her eyes. She was helping her dad in the rice fields and cut her little finger with a macete. The cut was deep enough to need medical attention everywhere but it was a much bigger danger for her. She had arrived with her grandma after more than an hour walk, losing a lot of blood. She needed to go to the hospital as soon as possible to avoid having her finger amputated due to gangrene. Despite the very long journey back to Puerto Lempira she arrived in time for the doctors to perform a surgery and take good care of her, saving her little finger.

Friendly Hospital

Italy - 2009

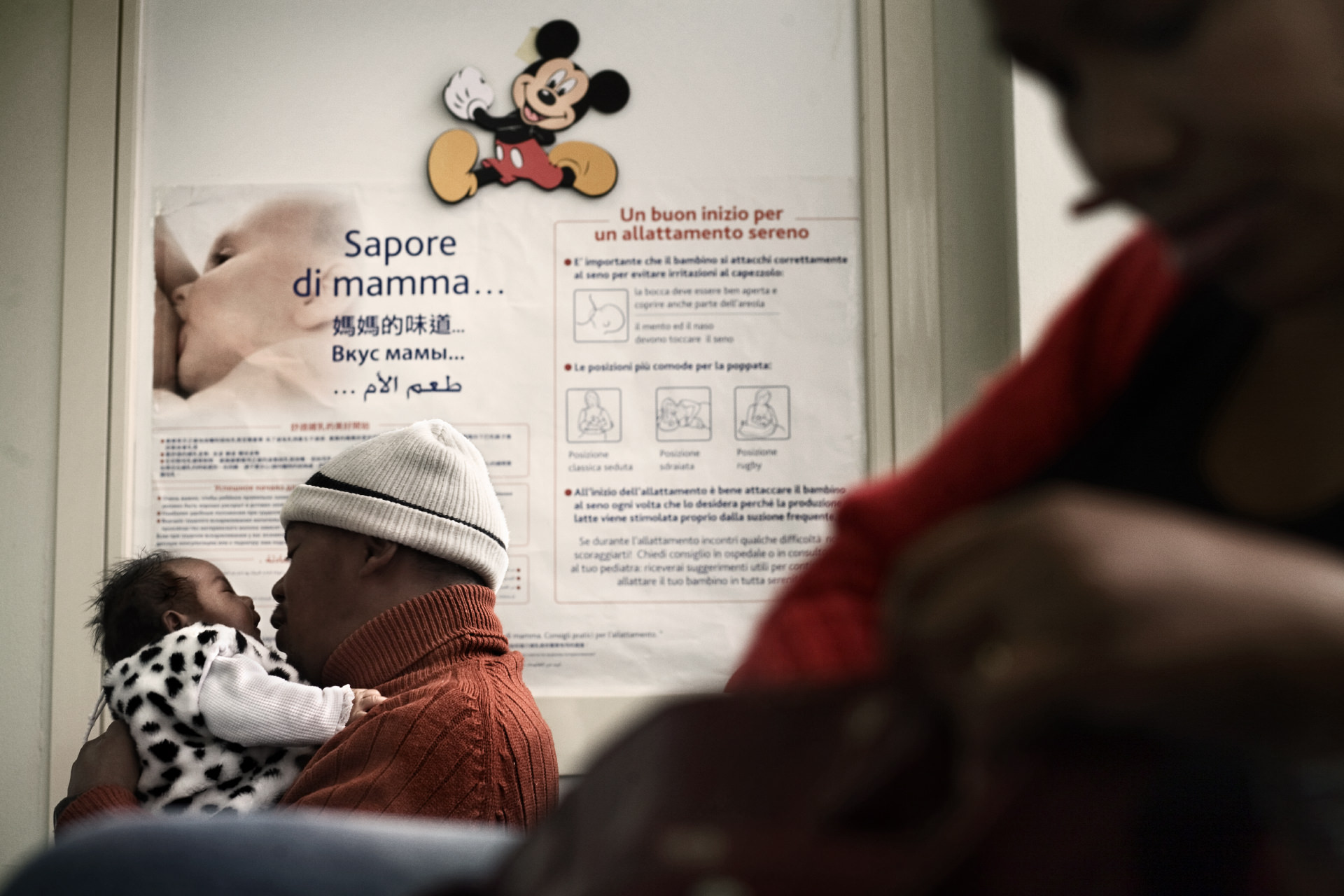

In Italy, immigration aroused and underlined the difficulties the Italian National

Health Service has had in terms of reaction and adaptation to the different

composition of society and to the needs of a new public of consumers. Political,

economical and cultural motivations often move migrant people to use the health

services offered by the hospitals only in case of emergencies and not to use those

available, for them as well, from the general practitioner of the National Health

Service. The low rate of use of these services and the health officers’ inability to

give an adequate response to the sanitary needs of the migrant patients have had

negative repercussions on the state of health of the migrant population, very often

insufficient if compared to that of Italians.

OSPEDALE AMICO /Friendly hospital) is a pilot project conceived by Imagine Onlus that

will be realized in partnership with San Filippo Neri Hospital in Rome. Aims of the

project are both improving the quality of the sanitary services offered to migrant

patients living in Italy and the relations between them and health officers. Taking

its moves from the “Migrant-friendly hospitals” experience, a tried and tested

European Union project, financed in collaboration with the W.H.O. and implemented in

12 hospitals spread all over Europe, OSPEDALE AMICO wants to define the activities

and the necessary arrangements to improve the services offered to migrant people and

the benefit they receive from the Italian National Health Service.

La moskitia. Gracias a dios

Honduras - 2008

La Moskitia is an area split between Honduras and Nicaragua and is home of the Miskitos indigenous minority. In the Honduran Moskitia, 75% of the population live below the poverty line. Women and children are the main victims of the sanitary emergency: 77 out of 1000 children die because of diarrhoea, malaria, tuberculosis and malnutrition. This rate of infant mortality is comparable to those of Ghana and Uganda.

There is a total lack of infrastructures, medicines and medical assistance. The only hospital is in Puerto Lempira, the capital of the Dipartimiento de Gracias a Dios. There are two surgery rooms but unequipped for most of the surgeries needed by the population. Most of the Miskitos live in small rural communities far away from the hospital and most of these communities do not have a “Centro de Salud”. Only the luckiest families can rely on small 15-horses-offboard boats but even with those boats it can take many hours to reach the hospital. This is a major cause of maternal-infantile deaths.

Another major cause is that there is no disease prevention at all and no monitoring on pregnant women as well. La Moskitia is very inaccessible. As a matter of fact it is reachable only by plane or by boat. There are no roads that connect it with the rest of the country. Water is the predominant element in the life of the Miskitos. Naturally it is a mean of survival but it is an enemy at the same time. In fact, Honduras is the first exporter of red lobsters in the USA and most of the business is run in this area.